BISCUITS IV: ENUNCIATION

BISCUITS IV: ENUNCIATION

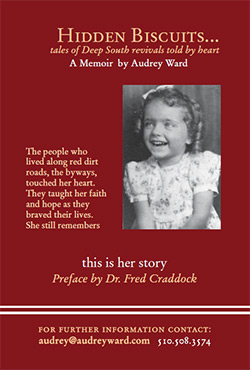

Audrey Ward

Illustration by Elizabeth Whybrow Leeds

A Biscuits’ Lesson on Enunciation from young Audrey, the voice of

Hidden Biscuits: Mama Keeps the Rules.

“Down a liberry’s wher a foun it…” Now don’t those words look as if they’d sound all soft and sweet? When I say them, I think they do. Mama, however, has a different opinion. When we’re travelling down south for revival meetings, which is nearly all the time, she keeps track of when I slip into speaking Southern.

But just try it yourself. Words are a lot easier to say here in Alabama. The way we’d say it in California, “Down to the library’s where I found it” (though we’d say ‘down at)—hard t on to, replaced by an a that slides through like uh. The is left out entirely. No extra twist on library, that -rar sound making your lips pooch out like a kiss and then straighten back right away in a flat smile for the y. It’s work. With where said wher, it comes out like a cat’s purr. And instead of a pokey I? That soft a once more.

To her credit, Mama doesn’t argue when I slip into Southern Talk. She just immediately snaps the Alabama right out of me by saying in her quiet voice, “Your Aunt Dorie won’t understand you.” Auntie Dorie lives in California. “In Alabama, it’s lovely to speak like this, but most folks here don’t visit up north and out west like we do.”

Then, as if she’s reading my mind which she can be mighty good at doing, she adds, “And if you talk like this only when I’m not around, people will think you’re mimicking them.” She settles me down. “That would be disrespectful.” Mama knows I’m disgusted by disrespect.

There’s another phrase–listen to this–“Na ya’ll take good care a auvr chirrun.”” Na for now, makes the same sound as our, and when it’s said the way Mama insists, it feels like you have a Mason jar lid wedged in your cheeks. But when folks here say auvr, it’s soft and runs right into chirrun, taking the hard edges out of the word children. Some people manage a quick hint of an l sound just before the r’s, but usually they don’t bother with tongue-to-the-top of the mouth for that.

One word we probably hear most often is Jesus. We say it with the wide-grin-mouth Je dropped to the shush-like sus. Right. If you say it Southern, though, it comes out like a cry: your mouth falls open with a slight J followed by aaay falling to a zus. Usually the last five letters can’t even be heard, but the sound that arrives can be understood: throw out a lifeline, somebody, send for help.

Talk resembles the weather, that’s how I think of it. In San Francisco, it’s usually cool and crisp. Summer, winter, the temperature hits the same level, somewhere between 50 and 70 degrees. Even places in California where it’s hot, there’s no rain during summer months, so hot or cold, there’s still a snap to things. The biggest change anticipates a lot of rain in winter, but the feeling remains the same, cool and crisp. And that’s how their words sound. The l’s, t’s, r’s,d’s plus all the vowels, are given their due enunciation. Carefully, like Mama says the word enunciation with a sharp e starting it off.

Not in the South. Here, it goes to 90 and even 100 degrees and over in the summer. A quick rainfall in the afternoon makes the red earth with tiny flat pebbles sprinkled over it all steamy. Then the air settles soft and thick and that’s how the words are, too. Soft, thick, and delicious as one of Eddylyn Jackson’s honey lemon cookies just out of the oven.

Mama also likes to remind me that what you say matters even more than how you say it. She always adds Jesus’ words when he reminded folks that what comes out of your mouth tells anybody listening what’s in your heart. That stops me from being a smart aleck.

You can’t slip anything by my Mama. She listens. Grammar, too. Everything has to “agree.” The plural with the plural, the singular and the singular, and of course negatives can’t step on each other. Daddy gets away with it, though, and I know that irritates Mama.

She never talks about it, but once (an Alabaman would say ‘oncet’, they don’t put on the brakes so fast), Daddy said “He don’t never come around,” talking about a local pastor. Mama corrected him quick as a wink ...doesn’t ever? Daddy didn’t say another word. He just left the trailer and gave her the silent treatment for a few days. Mama cannot stand the silent treatment.

Sometimes I wish she’d let me talk like I want to. But then one day I noticed another mother with her three little kids at the Piggly Wiggly grocery in Brantley. The woman’s muddy-water-looking hair hadn’t been combed or kept up but just happened on her head. The stained, shapeless dress hung over her could’ve been a night gown. Her eyes hid in her unbaked-biscuit-dough face but her thin lips yelled at her tiny boy—at least he looked tiny next to her—”Doncha neva sass me, ya brat. Na shut up.” Made my stomach jump.

That’s when it came to me that my Mama is right near perfect. Or, as they’d say here, raht neah per-fec. She’d wash my mouth out with soap if I said brat and shut up. She’s a Mama to feel mighty thankful for, I tell you. And I can say that from my heart.