BISCUITS TO LIVE BY

Audrey Ward

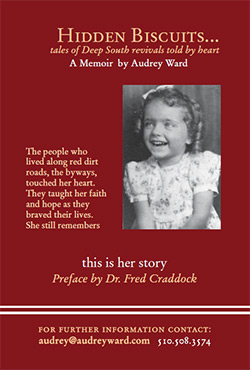

As I explored in Hidden Biscuits…tales of Deep South revivals told by heart, many of the Appalachian people of the Deep South “got free” in the Spirit when they were in the church and gave themselves over to a language of their heaven. As a child in their midst, I accepted their spiritual fire in the same way I experienced them, with a brim full heart, a love and confidence that some kind of mysterious power lifted that load they’d carried into the church house. Oh yes! Lay that burden down. And Dr. T.M. Luhrmann, professor of anthropology at Stanford did that for me as an adult: shifted a load of embarrassment about my past that I’d long assumed.

Certainly, in my child’s innocence of loving the people, however they expressed themselves, I omitted the comments from the rest of the world. But I also experienced that unexpressed shame at an internal level, dropped like so many crumbs and swept into a back corner.

I was out of the country when Dr. Tanya Luhrmann’s op ed piece appeared in the New York Times but my buddy Herb Gold left a message waiting for my return: Audrey, you must read 18 August (2013) editorial, Why We Talk in Tongues! Luhrmann had published “When God Talks Back,” in 2012 about Evangelicals of whom some practice glossolalia, a spiritual exercise of speaking in ecstatic speech during their prayers.

Dr. Luhrmann writes in her Times’ column that studies of people in Buddhist meditative states access the same level of non-decision making consciousness as those who speak in tongues. Of course it can also be faked she assures the reader (for example, just say “I should have bought a Hundai” rapidly10 times); tongues can also be perfected. But because this kind of worship involves a more emotional event does not mean that the results are less than true edification for participants.

In the Preface of my memoir, Hidden Biscuits, Dr. Fred Craddock, himself born in Appalachia and returned there after a high profile career as a professor at Candler School of Theology, Emory University, writes that this is, after all, an “oral culture, not a script culture…in an oral world in which words were not read but were spoken, were heard, were passed along or were stored in silence.”

Many of the participants in our revival nights did not have an opportunity to learn to read or to write. And during the 40’s and 50’s in the absence of electricity, even the possibility of a radio was remote.

When I talked with Dr. Luhrmann in her small sturdy office, mahogany trimmed windows looking out over a courtyard on the Stanford campus, I said that words were awe inspiring for these people. “Why?” she asked, genuinely interested. I responded, “They didn’t pour through 100’s of words every hour, or thousands, perhaps, in a day.”

As Craddock describes these scenes:

…seldom does one hear the cracking of the spine of a new book being opened…for many of the folk in these stories there is only one book, the Holy Bible, King James Version. They love to gather, they love to sing, they love to pray, but when the Evangelist mounts the pulpit and opens the Holy Book of warnings and promises, they love to listen. They have only one question: Is there any word from the Lord?

So imagine, then, what being able to be lifted into an altered state in which strange words come forth from one’s own mouth could mean to a person deprived of books. Words said to arrive directly from the Spirit of the Living God.

Now I’ve never craved such an expression, but I understand why someone would. They were considered ignorant in the outer world, but here, they were comforted and ascended into a higher realm. Here, they were confident of their place by way of their devoted participation. They may have had little of what could be counted but they had what counts: Spirit, tears, and laughter in the sheer joy of their Master.

“Time to end the prejudice…” Luhrmann announces at the end of her column. And I heard her, through an overlay of shame for 60 years of my life. Children know, even when they aren’t told anything at all.