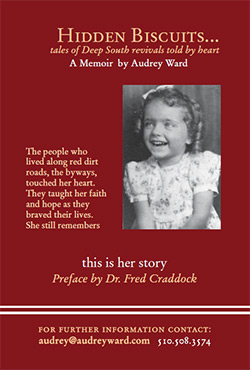

Audrey Ward

My memoir (Hidden Biscuits…tales of Deep South revivals told by heart) tells of a late 1940’s—50’s childhood traveling in an 18’ trailer through the Deep South. Running water? No, unless you count the creek that ran alongside some red dirt roads. Electricity? We did park next to the church and hook up, but often in the late 40’s the lines didn’t reach that far out in the country where only lightening bugs, crickets and hoot owls inhabit the night. It goes without saying that there was no indoor bathroom.

And yet, in writing this narrative I became acquainted with my family of that era once again and realized that the shelter they provided was a true comfort station. One where the downward glances of those outside our circle and disparaging remarks inside our circle were silenced. My father’s upwardly mobile sister and brother in San Francisco–emigrated from Russia through Canada, therefore listing themselves as British–considered our family’s traveling life a blight on their resumes.

The roads we traveled through the South were mapped out by my father, Bill. I learned to read those maps before I could read words. But it took a long time to hear what was stuffed deep inside the silence. Mother was with us, too, though in the 40’s and 50’s Mother was not the one who set the course. As I moved away from childhood and the church of my early years, profound discoveries emerged when I began to ask questions.

They are questions camouflaged by layers of fear, shame and suspicion: Daddy, a traveling Pentecostal Evangelist? Elmer Gantry immediately looms, slick salesman of a preacher man immortalized by Burt Lancaster.

But my dad was the real deal, not a celluloid scoundrel. We were on the road to tell the Good News, together: the Preacher, my musical mama, older sister, and I, the child called Spark Plug. “She gets things goin…” daddy would say as I jumped up on a box to lead everybody in singing. Curls dancing, eyes flashing, I never imagined myself a star, though people constantly compared me to Shirley Temple. No, no, stardom would indicate Pride: “I’m working for Jesus.” That’s all.

But it’s always the people of the red dirt roads, the byways, who crowd my memories. Sister Bernice, Brother and Sister Payton, Brother Kenny, Sister Irene, though they said all these names in twice as many syllables as I do now. Drawn out, the familial address turned into an embrace, not in physical contact mind you, but in a Father God and Lord of All sense of adoring kinship.

Where else could bone weary workers of meager resources find an atmosphere of consideration, protection and encouragement than in the church house? Not in the unventilated rooms of the mill, or the misery of long hours in the peanut patch; not under the scrutinizing glare of a landowner’s eyes on a sharecropper. No one who paid a dollar a day at the cotton field cared when fingers were torn and bloodied from the boll’s vicious thorns.

In the morning when I rise, give me Jesus, the folks on the straight backed hard benches sang. Their faith in this presence was the power by which they survived. And when Revival came to town every summer, they were sure to be lifted up above the shadows of worry and regret. Ready to face another year.

During that era in the South, Jesus magic was pervasive. It worked like vapor rising from sun soaked ground when afternoon showers drench the soil. All His words printed in red for those who could read their King James Bible and all His pronouns capitalized. And their faith held fast to His hand with the grip of a deathbed promise.

Daddy’s preaching enhanced strength and excitement in what was already there. Even sinners who didn’t frequent the local church could be enticed to join in the hum of Revival. The Preacher’s evocative style of being one of them, surrounded by our gospel music, went into the cotton fields and mills with the people, singing the message all the day long.

There were good reasons, then, for me–that little child who led them–to shy away from questions: no doubts allowed about the all-knowing, all-powerful God expressed as Jesus. Later, as a master’s student in divinity at Berkeley Theological Union, I did tell the truth about my early life. The disdain and the conjecture of ignorance found in such an emotional sort of religion became a stalking presence in the classroom. The worldly tolerance of my über-liberal classmates was summarily abandoned.

Plunging into my family’s stories so much later, however, provides a stream of revelations: chief among them, the comfort my parents sought to surround us with in the midst of a judging culture. That understanding comes at the price of also discovering the internalized shame and slander of being assumed to be a child of poor unholy trash.

Finding the gems in the rubble of disdain—faith, hope and love that righted wobbly lives—makes it worth the research and the writing, The communities we visited still bear witness to their being sustained through hard times by those revival nights. And I’m willing to explore the roads my father’s hand mapped out so long ago with a refreshed appreciation for the people, their ways of learning, their keen intelligence, and the source of their confidence: You can take all this world, but give me Jesus.